Ultra-Processed Foods: The Good, the Bad, and the Not-So-Ugly

We know that not all foods are equal. Be it boiled potatoes or potato chips, which are both made from the same spud, yet are very different.

You see, unless you eat your produce straight from the ground (e.g. potato right from the furrow), any action you take to prepare your food counts as processing. Yes, even the basic produce care such as washing, cutting, peeling; it’s minimal processing, sure, but processing nonetheless.

What are UPFs?

To address the differences in processing, a system called the NOVA food classification system was developed. It divides products into 4 groups based on the processing they’ve gone through. It goes as follows:

- Group 1: Unprocessed or minimally processed foods.

- Group 2: Oils, fats, salt, and sugar

- Group 3: Processed foods

- Group 4: Ultra-processed foods

The loudest talks, however, lately have been particularly about the last group - the ultra-processed foods (let’s call them UPFs), and how bad they are for us.

The definition of the UPFs goes as:

industrial formulations made entirely or mostly from substances extracted from foods (oils, fats, sugar, starch, and proteins), derived from food constituents (hydrogenated fats and modified starch), or synthesized in laboratories from food substrates or other organic sources (flavor enhancers, colors, and several food additives used to make the product hyper-palatable). [1]

In short, these are products that barely resemble the foods they were made from.

That would include salty, fatty snacks (like chips), most confectionary (candies, cookies, ice creams), breakfast cereals, energy drinks, ready-made meals (like pizzas, hams, sausages, even vegan meat alternatives), as well as others.

Let’s take the already mentioned potato as an example. In itself, a potato isn’t processed, yet when you bake it, it becomes processed. If you turn it into French fries or chips, it crosses into ultra-processed territory.

Similarly, an example can be set with peanuts. You can eat them as they are, in which case they are minimally processed. Add salt or sugar, and now they’re processed. But peanut butter cookies you buy in the store - you have yourself some UPFs.

Why are UPFs bad for us?

Research (and thus also media) has jumped on the “UPFs are the devil” bandwagon. To support that, many studies indeed have shown that eating more UPFs is linked to all sorts of negative effects.

One umbrella review of meta-analyses found that eating more UPFs was associated with higher all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality, and type 2 diabetes (will refer to it as T2D further on). It also showed a connection between UPF consumption and being overweight, and even a risk of it affecting our mental health. [2]

Another systematic review found that UPF consumption was linked to a higher risk of developing T2D, hypertension (i.e. high blood pressure), hypertriglyceridemia (i.e. high triglyceride concentration in your blood), low HDL cholesterol concentration (this is often referred to as the good cholesterol), and even obesity. [3]

The next logical question that should follow is: why do UPFs seem to be so bad for us?

One answer that is commonly used is that after all that processing, often what’s left in these foods is high saturated fat, sugar, and salt content - all things we know aren’t good for us when consumed in excess. But here’s the twist: some studies show that the harm of UPFs remains even after accounting for these factors. For example, one study found eating more UPFs was linked with higher cancer risk, and it remained statistically significant even after adjusting for diet quality. [4] It makes us think that probably something else is at least partially at fault here. More research is definitely needed to figure it out.

Another issue that arises from high UPF consumption is called a displacement effect. By eating lots of UPFs, you’re likely not eating enough nutrient-rich foods like fruits and veggies. So what happens is you eat a lot of saturated fat, sugar, and salt, and not enough vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and other nutrients that allow your body to function properly.

Are all UPFs equal?

From all this talk, it might seem like UPFs are the cause of all evil. But here’s the kicker: not all UPFs are equal. Some might even do us some good.

One issue at hand is that many studies lump all UPFs together. That’s helpful for seeing overall trends; however, by doing so, we might be missing important details in the process. Some researchers are trying to tackle this by breaking UPFs into subgroups to see how the effects of them differ.

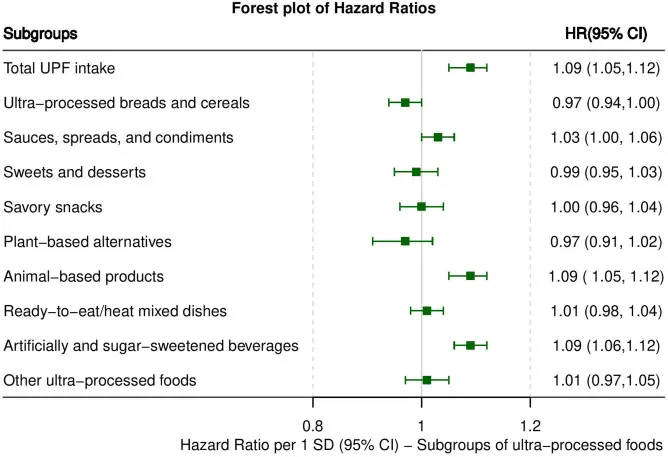

For example, one cohort study found that the biggest risk of total mortality comes from ready-to-eat meat, poultry, and seafood products. [5] Another cohort study showed similar results, where animal based UPFs, and artificially and sugar-sweetened beverages were all highly associated with increased risk of multimorbidity (cancer, cardiovascular disease, T2D). Sauces, spreads, and condiments also showed a link with higher multimorbidity risk. On the other hand, ultra-processed breads and cereals seemed to be less harmful, as people who ate them had lower disease risk. [6]

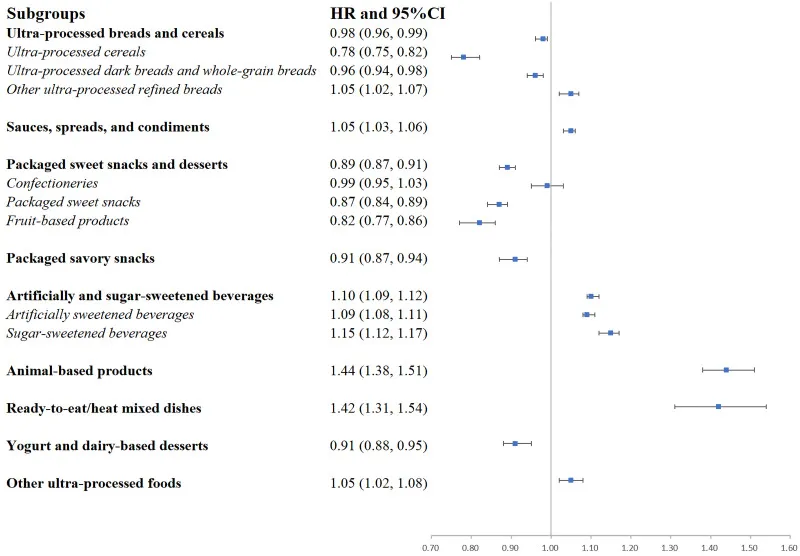

In a different study, a higher UPF consumption was associated with higher T2D risk. When doing subgroup analysis, here again, the higher risk of T2D was seen for those consuming sauces, spreads, and condiments; artificially- and sugar-sweetened beverages; animal-based products; as well as ready-to-eat or -heat mixed dishes, and even refined breads. Yet consumption of ultra-processed dark and whole-grain breads and cereals; packaged sweet and savory snacks; fruit-based products; and yogurt and dairy-based desserts showed lower risk of T2D. [7]

In simpler terms: it looks like not all UPFs are as equally detrimental for us. From the available research, the biggest culprit seems to be ultra-processed animal foods (such as bacon, hams, sausages, nuggets, etc.), artificially and sugar-sweetened beverages (like the sodas we drink), as well as different ultra-processed sauces, spreads, and condiments. On the flip side, certain breads and cereals don’t seem to do as much harm.

What should we do with this info?

So, what does this all mean to us, people who shop in the grocery stores filled with UPFs? Ideally, we’d all eat mostly minimally processed foods; however, the reality is what it is. Many of us include processed and ultra-processed foods in our diet. Some less, some more. From the data available to us, it seems we might all benefit from cutting back on sodas, sauces, spreads, and animal-based UPFs.

That being said, let’s not forget that nutrition guidelines still apply even if you’re choosing to include UPFs in your diet. That means, try to limit your sugar below 25 g, salt below 5 g, and saturated fat below 10% of your energy intake per day. Also, remember to consume plenty of fruits and veggies (at least 500 g per day). And to conclude, I want to say that science is always evolving, and so will our understanding of the UPFs. For now, though, it looks like you should be cautious of some UPF’s more than others.

References:

-

ECU Physicians. (2018). The NOVA Food Classification System. Retrieved from https://ecuphysicians.ecu.edu/wp-content/pv-uploads/sites/78/2021/07/NOVA-Classification-Reference-Sheet.pdf

-

Lane, M. M., Gamage, E., Du, S., Ashtree, D. N., McGuinness, A. J., Gauci, S., et al. (2024). Ultra-processed food exposure and adverse health outcomes: Umbrella review of epidemiological meta-analyses. BMJ, 384, e077310. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-077310

-

Vitale, M., Costabile, G., Testa, R., D'Abbronzo, G., Nettore, I. C., Macchia, P. E., & Giacco, R. (2024). Ultra-Processed Foods and Human Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Advances in Nutrition, 15(1), 100121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advnut.2023.09.009

-

Fiolet, T., Srour, B., Sellem, L., Kesse-Guyot, E., Allès, B., Méjean, C., et al. (2018). Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: Results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ, 360, k322. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k322

-

Fang, Z., Rossato, S. L., Hang, D., Khandpur, N., Wang, K., Lo, C., et al. (2024). Association of ultra-processed food consumption with all cause and cause specific mortality: Population-based cohort study. BMJ, 385, e078476. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-078476

-

Cordova, R., et al. (2023). Consumption of ultra-processed foods and risk of multimorbidity of cancer and cardiometabolic diseases: A multinational cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health – Europe, 35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100771

-

Chen, Z., Khandpur, N., Desjardins, C., Wang, L., Monteiro, C. A., Rossato, S. L., et al. (2023). Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Three Large Prospective U.S. Cohort Studies. Diabetes Care, 46(7), 1335–1344. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc22-1993

Try Nutriely for free.

Download our app and start your free trial with all premium features included.